It is not unusual for Greeks to consider elections always around the corner. It is not only in their nature to view politics as a volatile environment; it is also Greek politics that, traditionally, has been a field of increased tension; excessive partisanship kept feeding instability and irrationality in a non-stop fashion.

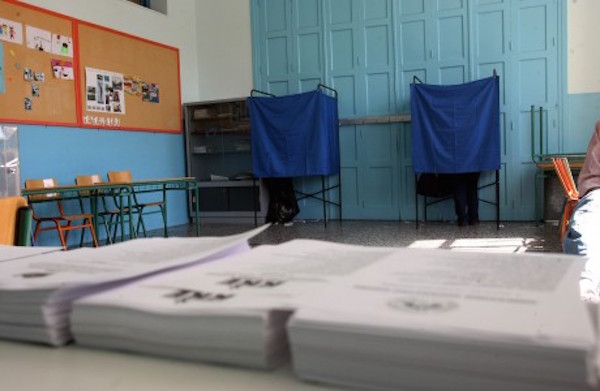

Any information kit a foreigner receives on the country, diplomat and investor alike includes the same information as regards elections. They usually happen on average every three years and politicians and voters do not bother distinguishing the agenda and pre-election dilemmas into local, national or European. Each time voters are called to approach the ballot box, it is always about ‘we’ vs. ‘them’ – with this dilemma best reflected on the leaders of the two leading parties. For both camps -usually formed on the centre-right and on the -so called- ‘democratic left’- the policies and the views of the ‘other side’ are always considered catastrophic; relevant aggressive arguments usually cite the lack of an adequate amount of patriotism, excessive populism, conspiracies with foreign power centres against local interests and an omnipresent tendency to fool the people.

Greek crisis has led to the fragmentation of political power and the formation of smaller parties in both sides of the political spectrum. However, even with political power scattered amongst various maverick or opportunistic figures, the political game continues to be played amongst the two major players, currently Antonis Samaras and Alexis Tsipras, who have proved that they can effectively serve political juxtaposition all the way towards its dead-end. Traditionally, dilemmas were formed around internal agendas and local players. However, during the Greek crisis, for the first time, external players (EU leadership, lenders, markets, foreign executives) are considered part of the election equation. Do they really play a role? In so far they contribute to the scare tactics of local political clientele, they come in handy; both sides would agree on this one. In other circumstances in the past, any foreign statement on Greek domestic affairs would be a dire intervention into local political dialogue.

Samaras and Tsipras are two very different personalities. The generation gap is also quite present, a fact that the Premier’s spin doctors are well aware of; hence the limited times Antonis Samaras is allowed to appear next to the main opposition leader, either in parliament or on other occasions. Publicly distributed photo opportunities are scarce, originating only from the early days of Samaras governance, when the Premier was running scheduled meetings with opposition leaders as part of his effort to form the coalition. So consensus is out of the question. The extreme preconditions that may come in play if this process was ever mobilized would confirm the impossible nature of the task.

Both leaders express different perspectives to contemporary situation, having two quite distinctive roles: Samaras as the chief manager of the Greek crisis and Tsipras as the leading political figure who preaches the anti-austerity option. The mistakes of the former feed Tsipras’ political strength, whose obvious policy indecisiveness and reluctance to govern sustain Samaras in the prime minister’s post. Hence, the agenda of the juxtaposition is limited to don’ts, lacking the do’s. It is common ground amongst Greeks that if the Presidential election were not around the corner (due in Feb 2015), Alexis Tsipras’ chances to govern any time soon would be significantly less (GPO in its latest poll found that 63% of voters still find SYRIZA unprepared to assume governance).

So, how probable snap elections are? Greeks remain divided on the matter, according to most opinion polls. If allowed to speculate, I would say that those who favour elections (around 42% of the electorate – excluding various local or international business interests) do so for a variety of reasons; three types/arguments could stand out as the most important:

1) The Realists: They are dissatisfied by the way government is handling the crisis, delaying structural changes, lacking a coherent strategy to fight injustice, corruption and fraud and mark a restart of the ‘new Greek economy’.

2) The Frightened: They are scared about the future that seems increasingly dictated by Memoranda and German’s persistence on austerity; they strongly believe that nothing will change and state agencies will continue sucking money from their salaries and pensions.

3) The Lefts: They genuinely hate Samaras’ guts and believe that a hardcore centre-left approach (also through a different geopolitical prism) would be more beneficial for the country as a whole.

Voters view Samaras-Tsipras conflict with interest trying to figure out whom to trust. In May’s European elections (that, despite strong partisan rhetoric, allowed for a rather loose voting), a good number of smaller parties managed to maintain a presence above the parliament threshold (3 per cent).

Voters witnessed a brand new party, ‘To Potami’ [The River] (led by a television journalist who is preaching the grassroots approach) entering the political realm and gaining 6.6 per cent of the electorate even before securing a strong inner-party organization. They also watched ‘Independent Greeks’ losing a significant part of the party’s power (gathering 3.5 per cent), Golden Dawn maintaining a controversial (and in my mind largely non-partisan) 9.4 per cent and finally the all-centre-left coalition ‘Elia’ [Olive] marking a rather weak entrance in the political field (8%).

Since then, polarization and harsh political talk have boosted the power of the two major players, raising a polarised two-party sum up to almost 55% (57% in June 2014 elections), still significantly less, however, than the vast 77% recorded in 2009.

So, where do voters stand for the moment? According to the latest opinion polls by polling companies/institutions and their media clients, the gap between SYRIZA and ND ranges between 3.7 – 7.5 percentage points:

> KAPPA RESEARCH [To Vima]: SYRIZA 27.4%, ND 23.5%, Golden Dawn 6.4%, PASOK 5.8%, To Potami 5.6%, Communist Party 5.3%, Independent Greeks 3.8%.

> eVOICE [Eleftheros Typos]: SYRIZA 21.2%, ND 17.5%, Golden Dawn 5.3%, Potami 4.6%, Communist Party 4.4%, PASOK 3.9%, Other 8.3%.

> METRON ANALYSIS [Parapolitika]: SYRIZA 25.7%, ND 19.8%, To Potami 6.9%, Golden Dawn 5.3%, KKE 4%, PASOK 3.4%.

> GPO [Mega TV]: SYRIZA 26.7%, ND 20.2%, To Potami 6%, KKE 5.7% Golden Dawn 5.7%, PASOK 4%, Independent Greeks 3%, LAOS: 2.1% ANTARSYA: 1.6%, Other: 4.7%, Neutral/Void: 2.1%, Undecided: 18.2%

> MACEDONIA UNIVERSITY [SKAI TV]: SYRIZA 27.5%, ND 20%, To Potami 7.5%, Golden Dawn 6.5%, Communist Party 5.5%, ELIA 4%, Independent Greeks 2.5%, Democratic Left 0.5%.

> PULSE [Pontiki Weekly]: SYRIZA 27%, ND 22%, Golden Dawn 7%, PASOK 6.5%, To Potami 6%, KKE 5.5%, Independent Greeks 3%, Democratic Left 1.5%, LAOS 1%.

In people’s minds, coalition head Antonis Samaras remains the most suitable for the Prime Minister’s job (although the gap is closing with Tsipras), whilst, in terms of popularity, his junior partner Evangelos Venizelos is almost at the end of the list (22.8%), just above imprisoned Golden Dawn leader Nikos Michaloliakos (11.6%) who follows at the bottom. The three leading figures are: Alexis Tsipras 42.8%, Antonis Samaras 41%, Stavros Theodorakis 40%, followed by Fotis Kouvelis 34%, Dimitris Koutsoubas 33.6% and Panos Kammenos 29% (source: GPO/Mega).

Despite everything, more than 50% of citizens continue to stand against early elections, arguing that they would have a negative effect to the country’s economy and society in general. Moreover, the recent harsh messages by Greece’s lenders and international markets have aimed at two targets: firstly, to control Antonis Samaras’ appetite for heroics and unilateral anti-austerity moves and secondly, to give a taste of the real world to a hypothetical rooky government led by Alexis Tsipras.

It seems that these days, voters would prefer to remain plain citizens political leaders would spare from the bothersome of a snap election. However, for the time being, partisan interests seem to remain at the epicentre of developments, triggered by a weak style of governance demonstrated by the coalition scheme, PASOK’s collapse due to the low popularity of its leader as well as an inner struggle in the wider centre-left, accompanied by sporadic sideline activity by local centre-right political centres that once again see cracks on the country’s systemic superstructure.

Greece’s future is around the corner and the next 100 days will act as a countdown towards real change: of structural or partisan nature.